Thomas Szasz, a Hungarian-American academic, psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, suggested that “Every act of conscious learning requires the willingness to suffer an injury to one’s self-esteem. That is why young children, before they are aware of their own self-importance, learn so easily; and why older persons, especially if vain or important, cannot learn at all.” While there is truth in what Szasz is saying – I wonder if we might ask ourselves if we are creating the right conditions for learning which might circumvent apparent feelings of “vanity” or “self-importance” that could easily be manifestations of fear or mistrust of our own unnamed, unintended behaviours as teachers and leaders.

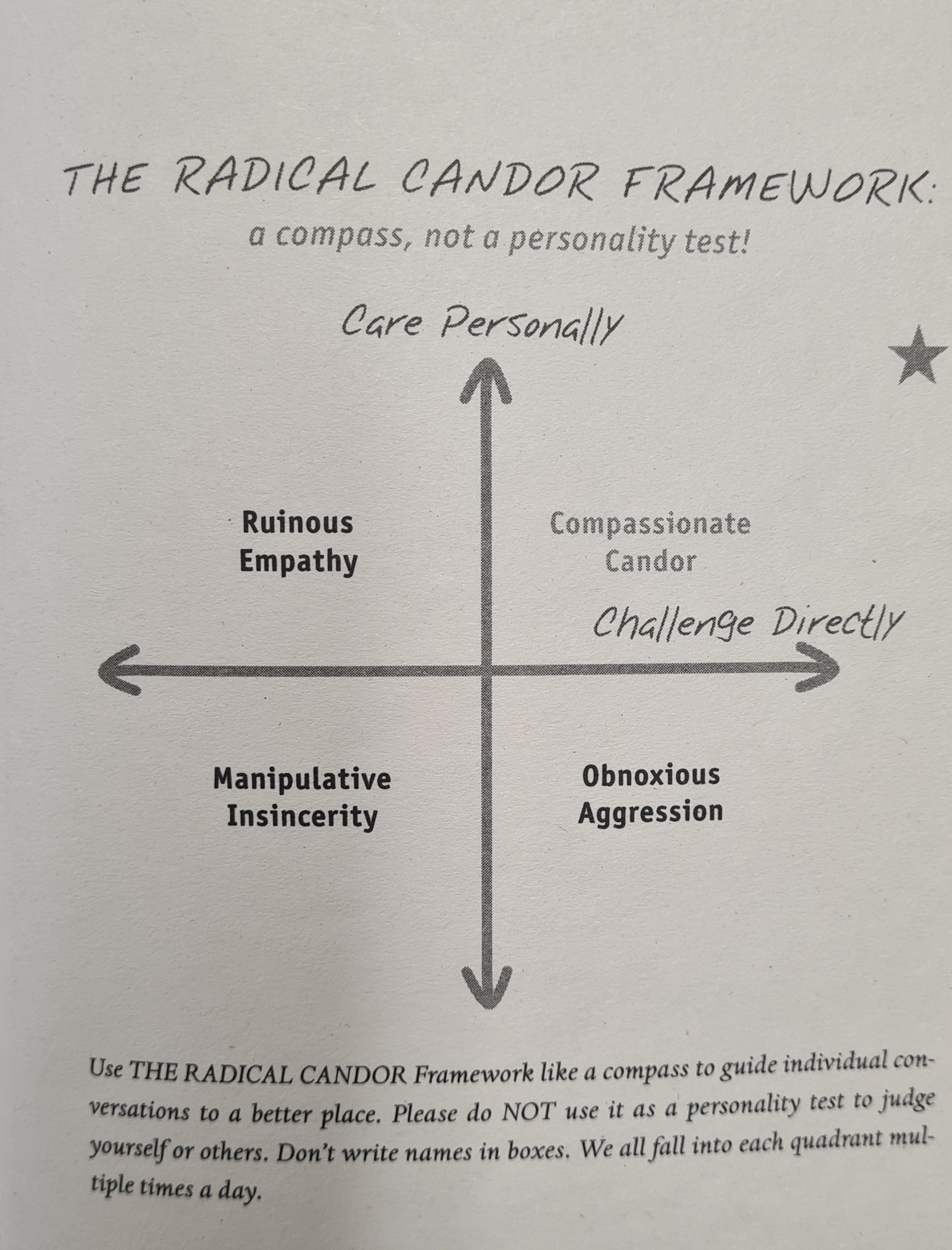

Warm Strict, from Doug Lemov’s book Teach Like a Champion asserts that there are two sides to creating the right conditions for pupils to flourish in a classroom that must exist in the same instant. Firstly, being “warm” – connecting to children, showing that you care, building relationships (quote of the year so far from TLaC 3 – “Teaching well is relationship building”) while simultaneously delivering on high expectations with considered, consistent and deliberate culture/instruction/feedback/praise – the “strict” side.

Lemov uses words like relentless, warm, gracious, caring and quotes Zaretta Hammond from her book Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain who talks of “Warm Demanders” and “active demandingness”. Hammond describes the over-effusion of empathy from a teacher whose lack of strictness or willingness to reduce their expectations as being a “sentimentalist” who “allows students to engage in behaviours that are not in their self-interest”. Lemov is careful to acknowledge the emotional burden the accompanies the word “strict”. Moving our minds away from connotations of compliance and steering us to a mindset where we might “prepare the child for the road, not the road for the child”.

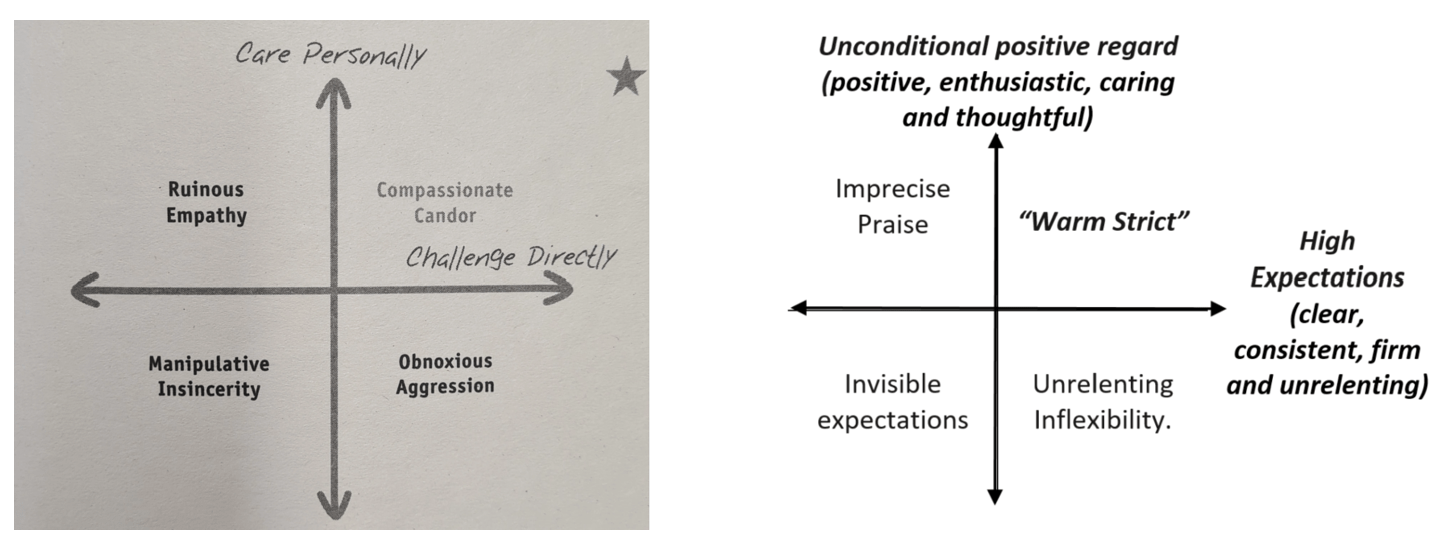

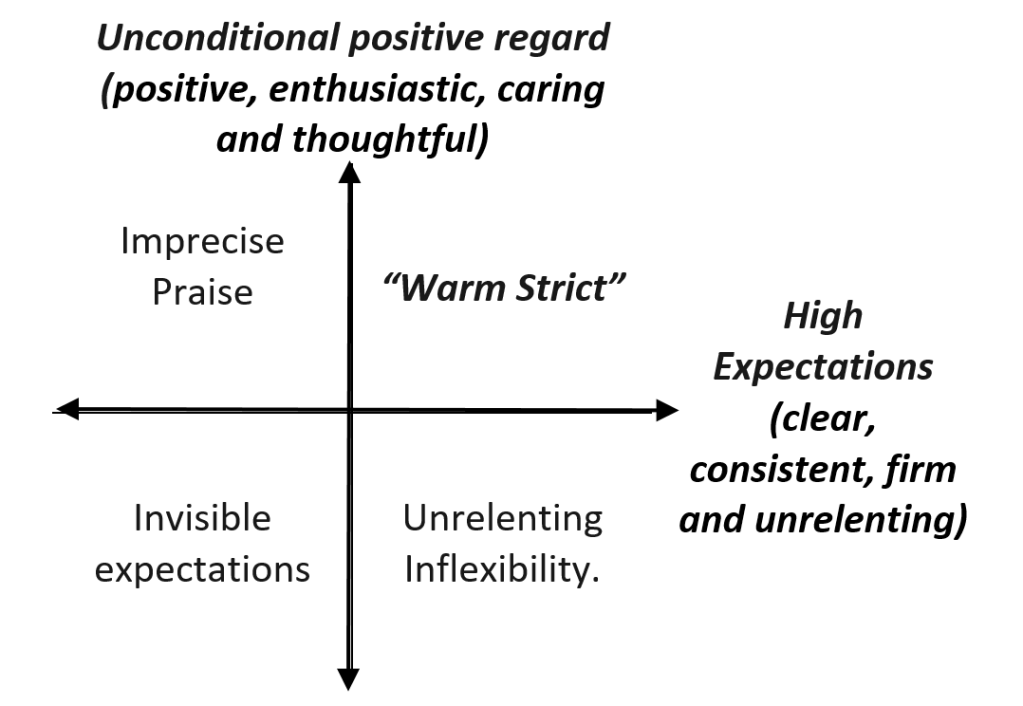

In the preface to the revised edition of Radical Candour (I will use the anglicised spelling) by Kim Scott, she offers the replacement title Compassionate Candour. Scott describes compassion as “empathy plus action”. In short, the book is focused on a quadrant whose two axes are based on “Caring personally” and “challenging directly” in order to encourage the best from the people with whom you work. Scott has labelled the four quadrants with behaviours and describes in detail in the book how these behaviours manifest in interactions in the workplace (see above image from Radical Candor, 2019, Kim Scott). Radical candour or compassionate candour is the essential ingredient which represents “the virtuous cycle between your responsibilities and your relationships” enabling you to learn the best ways “to get, give and encourage guidance”.

We can draw parallels between Lemov’s Warm Strict and Compassionate Candour as defined by Kim Scott: in both cases, if the first essential element can be boiled down to sincere human consideration, the second: challenging directly and holding high expectations must represent the feedback offered to make this happen. We might see clear links in the pitfalls of ruinous empathy where a manager favours caring personally without applying any challenge resulting in low levels of development and the potential risk of underperformance in the same way that we have seen how the “sentimentalist” in the classroom chooses “the short-term benefits to herself of satisfying personal relationships over students’ long-term success”.

In Radical Candour, Scott evaluates the quadrant through a number of prisms, including relationships, guidance, motivations and results. Each time, exploring how you might reflect on your own behaviours as you interact with your team – creating the conditions for your team or co-workers to thrive. Replacing Compassionate Candour with Warm Strict, we can look at the teacher pupil interactions through Kim Scott’s lens. We can begin to reflect on the effect that particular behaviours might have on the pupils in our classes and the resulting impact on our desired outcomes for that group of young people. Here I have attempted, somewhat clumsily, to recast Scott’s work focusing on teachers and pupils as opposed to adults managing one another.

Warm Strict is the optimal quadrant, where unconditional positive regard meets high expectations. This will favour conditions for learning that might reduce mistrust and engender attentiveness and risk taking. I see this a lot in classrooms in our school. As with Kim Scott’s diagram, these are not personality types, but a compass of behaviours that we might drift in and out of during the course of a day under the various pressures that accompany working in a school. As in Scott’s book, the idea would be to focus on ways of working which enable you to occupy the optimal quadrant as often as possible in work place or classroom interactions.

Imprecise praise might illustrate a situation in class where praise relates to person/personality and not actions or gives effusive or meaningless affirmations that offer little in the way of deliberate guidance. This might lead to a young person feeling inaccurately defined, labelled or constrained. This could be intentional, meant as a way to build relationships and trust, or it could be unintentional: as a result of a lack of deliberate planning and thought. We might very well care deeply but if the actions we take to demonstrate this are not linked to clear expectations it means that potential learning and relationships are built on shifting sands.

Invisible expectations might see us holding a pupil to account for something that is poorly or barely explained either in terms of behaviour or learning. This lack of transparency implicitly relates a lack of connection and creates unnecessary trap doors for pupils, and ultimately, for teachers. In the long term this will not only lead to poor relationships but learning is likely to be less effective as low or no expectations conspire with an absence of human consideration.

Unrelenting inflexibility tells a story, rich in expectations and clarity, but locked into the rigid stare of the long and unbending “my way” ahead. In this quadrant the paths to learning and behaviours are writ large on a single arrow. Learning might be strong but relationships will take time and may not flourish, some resulting barriers may lead to inattentiveness and rejection, leaving room to care more about the people that one might be keen to hold to account in a class.

In the title of Lemov’s technique number 60 Warm Strict and the tagline of Scott’s Radical Candour “how to get what you want by saying what you mean” a distracting curtain of assertiveness shrouds caring and thoughtful content and meaning. In order to ensure that your actions as pedagogue yield effective results, whether in training and developing adults in the work place or with educating pupils at school: remain fixed on achieving ascribed goals through high expectations and clear feedback. However, although the focus on development is keen, the message about personal investment is unambiguous. It is possible then, that by focusing on these similarities in human nature, that the old adage of balancing trust and accountability can find meaning here, within the pages of these books, across the generational divide.