Schools Week reported from ResearchEd18 that Sam Sims (associate research fellow at FFT Education Datalab) described Instructional Coaching as “probably the best evidenced form of CPD known to mankind”.

Bringing coaching to life in schools

— edited version originally appeared in the TES in 2019 (or was it 2018?).

Bringing coaching to life in schools.

There are a lot of lessons in life that can be drawn from music and cooking. Two that I have always particularly enjoyed applying to a variety of situations in work and at home are these: firstly, in music, it is often the silence or the gaps in the music that are the most difficult elements to get right and those which have the greatest impact on the listener. The second is from cooking and it is that food should be handled as little as possible in any given situation – overworked dough contracts and will not rise properly, over-whisked egg whites will go watery and lose their shape and shine, pastry will suffer from being exposed to hot hands for too long. In schools it is easy to fall into this trap in any number of different areas. Recently reported evidence in the field of data use suggests that some schools are putting the same dough through the pasta machine again and again but are we losing sight of the ingredients, their individual qualities and how we expect the end product to turn out?

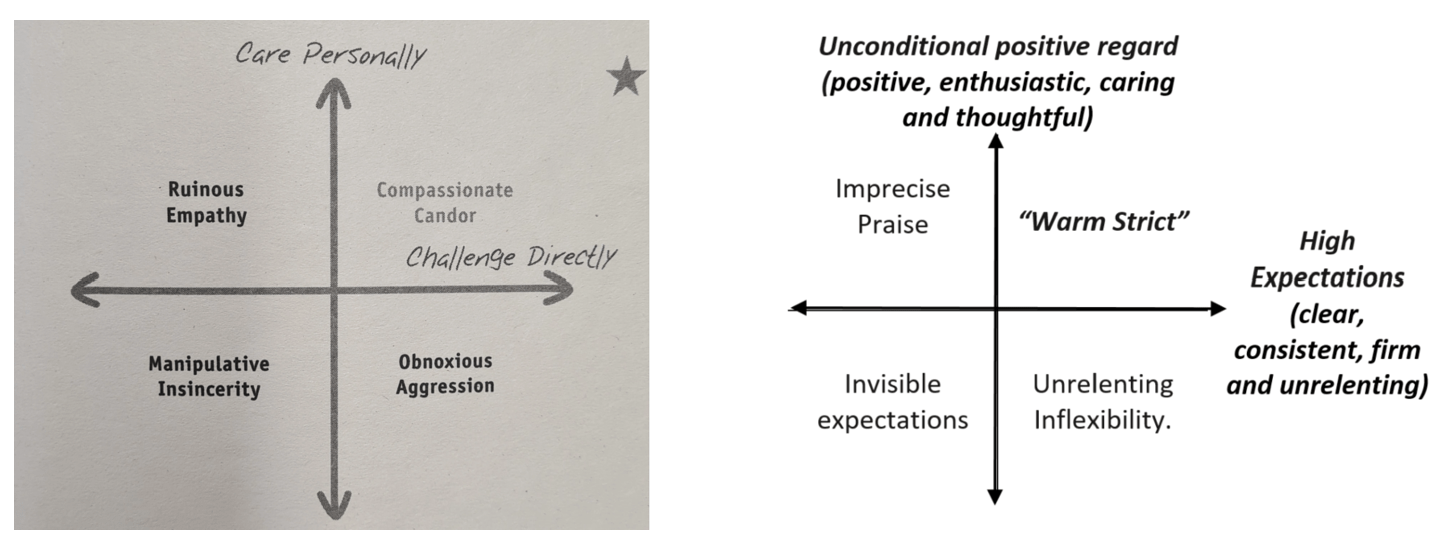

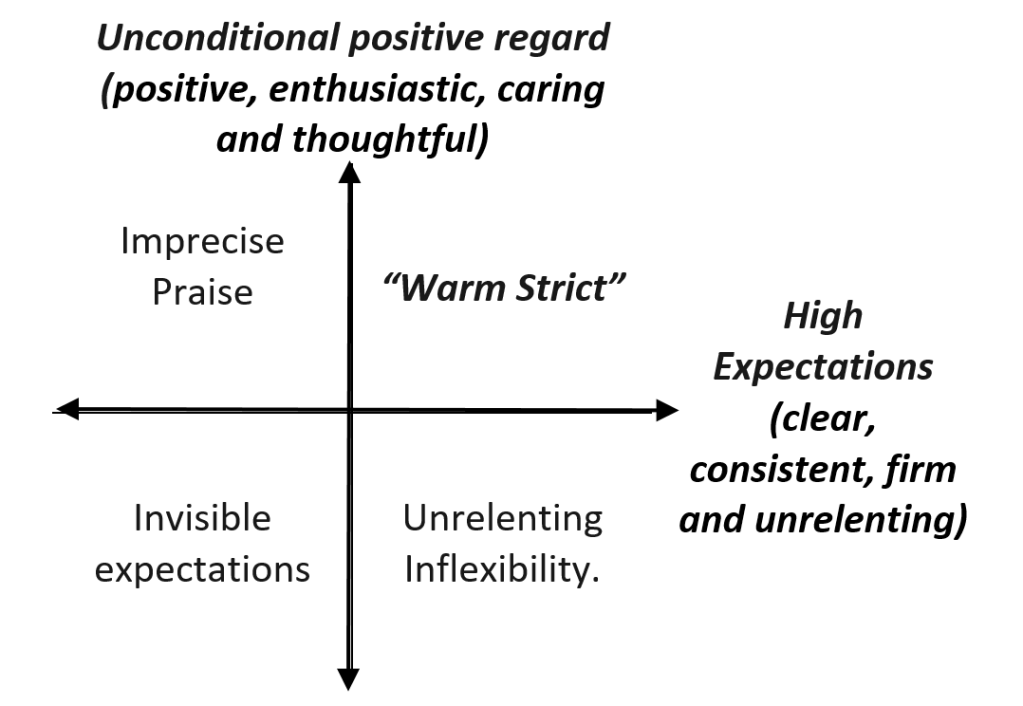

It is this question that I have been toying with in recent years as I have tried to develop and improve our school’s coaching model. The question really boiled down to this: Can we reduce the hierarchical nature of the quality assurance process by introducing peer support and coaching as the main way of improving T&L in a secondary school context? If we could improve the balance of accountability and trust, by handling things a bit less (and managing the pauses in notation with greater confidence) then I am convinced that we will enable growth and promote the development of all teachers. We could avoid the pitfalls of the QA pasta machine squeezing the goodness out of our best practitioners by giving them the opportunity to share their craft while they are still at the top of their game in the classroom. I want to be clear that there is a role for QA, we need to make sure things are where we want them, however it must be proportionate and effective, rather than a stifling and mindless approach which does more harm than good.

As a teacher and leader of MFL over the years I had taken part in and led triads of coaching and co-planning based loosely around the GROW model (Goals, Reality, Options, Way forward) and found real success in small pockets of willing participants and in faculty. As I moved into senior leadership, with responsibility for Teaching and Learning and CPD, the challenge became how to find a way of expanding this, in a practical way, to the whole school. When I got the job, our school was not one with open doors and sharing of best practice at its heart – it was not short on good practice but teachers retained a bunker mentality and insularity reigned supreme. This backdrop combined with the twin pressures of time, opportunity and the mystical reputation that this form of coaching has managed to garner, which can make some uncomfortable, meant that past rollouts had not met with widespread success at our school. Cue a T&L group which managed to convert a couple of sceptics, and resulted again in more successful triads and again further challenges in the face of time and external pressures. However – each and every episode put teachers in the driving seat and opened more doors in more classrooms. Shards of light breaking through the cracks that demonstrated this might be the direction to follow.

In October 2016 I went to visit Rodillian Academy Trust with Deputy Headteacher Andy Percival who had recently introduced coaches called Deputy Directors in Learning to his school. This idea chimed exactly with my desire to rebalance trust and accountability at our school. In addition, it offered extra T&L leadership possibilities. I spoke with the coaches, toured the school and learned an awful lot in that day and took away so much learning which I have subsequently (slowly) been able to manipulate into a contextually appropriate shape and implement at our school. In addition to this visit I have read widely on the subject and T&L in general. Of particular significance in shaping thoughts on the subject for me have been the following: David Didau’s “What if everything you knew about teaching was wrong”, Doug Lemov’s “Teach Like a Champion”, Bambrick Santoyo’s “Leverage Leadership” among others. The bright face of Twitter can, at times, provide a rich seam of edu-inspiration from generous teachers and leaders – the outward facing nature of social media being a force for good, where it does not stray into polarised non-debate and fact-bereft nonsense.

The process of implementation coincided with the creation of our new school – as we became part of the Trust. As a leadership team we each had a unique opportunity to rewrite policies and include new ideas. This was not going to be a “new logo on a display board” effort, but rather a root and branch re-working of the central levers of the school. In the area of T&L and CPD the coaching – and the Deputy Directors in Learning (DDLs) were going to form a central part of this plan. In the year 2016/2017 prior to launch in September 2017, a T&L focus group was formed to trial the various different “Teach Like a Champion” strategies that I hoped to include in the new policy, we trialled these in about 12 classrooms and teachers fed back. It would be the teachers who trialled these techniques that would end up interviewing for the DDL positions and they would have the language and the expertise already at their disposal to promote the style of T&L that would take our school forwards in September. It was at the end of this year, that a second unique opportunity presented itself via Swindon Challenge: a visit to a school in Accrington to do some Leverage Leadership training with Uncommon Schools.

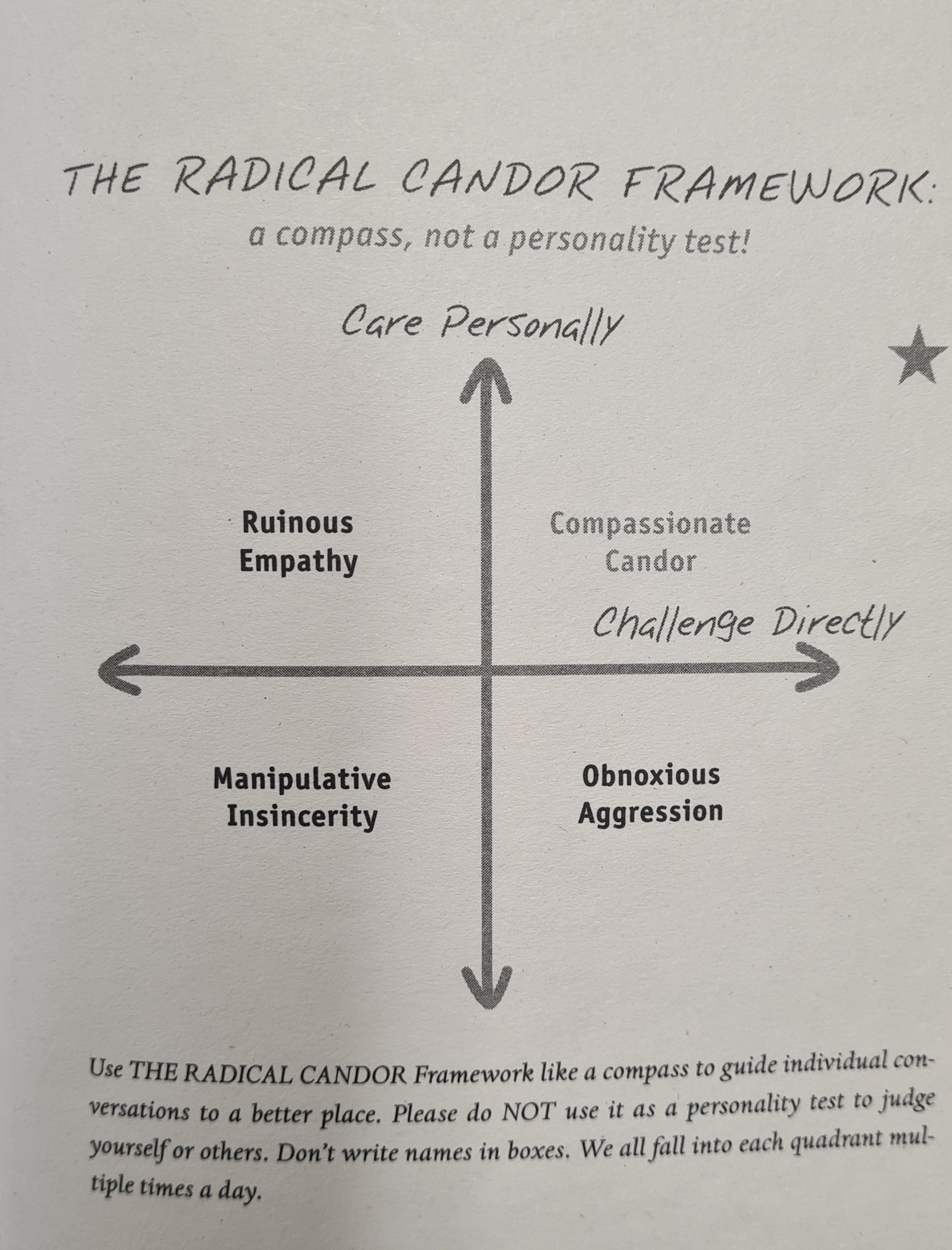

The DDL coaching strategy has formed part of the vast breadth of changes that our school has undergone – and can rightly be included in the list of impactful changes that have led to improvements. We have now clarified some of the processes and more closely aligned with the Incremental or Instructional Coaching Model as defined by Bambrick-Santoyo in “Leverage Leadership” (and another of his books called “Get Better Faster”). Instructional Coaching is about isolating one element of teaching practice to improve in an action step, through discussion with the coachee, which might then be honed and practiced. It reduces the gap between feedback and action – all the while retaining the excellent focus on questioning. We are using the six steps for effective feedback and, in response to requests, have set aside two Monday meetings a (short) term in the calendar to set up and review the “plan, practice, follow up, review” cycle that will take place in between. Each new revision to the model is trialled with the DDLs to assess practicability and timings, it has been so important to ensure clarity throughout the process and to make sure what we are asking people to do is possible on a normal timetable. We have rolled this out to all staff .

In terms of challenges, the scale of change that we have effected during this period has been significant and we are lucky to have had the support of a talented and resilient staff base. Also extra capacity from the Trust supported in year one of our launch – which provided invaluable sounding boards for us and access to excellent OLEVI CPD opportunities in their teaching school for many of our staff. The majority of the changes introduced, including the DDL coaching have been about harnessing the existing talents within the school, making very effective systems that do what they say on the tin and also reduce the load on teachers. We stopped grading lessons in 2015, and gave our lesson observations a developmental focus linked to a teacher-selected target. We have begun the process of reducing our reliance on traditional QA, we are not throwing everything out with the bathwater but simply trying to handle things a bit less and feel confident with the silences. The pendulum of trust and accountability has swung and we might dare to envision a situation where the instructional coaching model we are developing eclipses the requirement for simple evaluation style observations and our teachers can work together to bring coaching to life in schools.